March 15, 2018 - For the last few years, defaults have been generally benign (iHeart notwithstanding) and investor demand has been very robust. But presumably these dynamics will change – and when they do, what might be the impact on the loan market? That issue was discussed extensively Wednesday at an RMA Panel on the Leveraged Loan Market moderated by LSTA EVP Meredith Coffey. We recap main themes (and dispel major misconceptions) below.

First, on defaults. According to S&P/LCD, as of March 8th, the loan default rate sat at 1.7%, well below the long-term average of 3%. But, with iHeartCommunications bankruptcy on March 15th, the default rate should climb above 2.7%. Still, iHeart was long expected and isn’t even in the sector that gets the most buzz. Indeed, it is the retail sector – where Fitch is tracking a loan default rate of 8% loan today and expects 10% by year end – that has the most chatter.

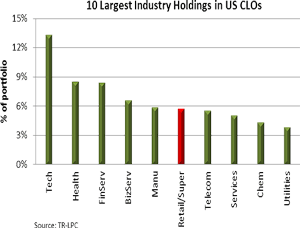

And that leads us to a major misconception we wish to dispel. The misconception: Lenders – particularly CLOs – have a large exposure to loans in the retail sector. As the LSTA Chart of the Week  demonstrates, the retail & supermarkets sector is the sixth largest industry exposure in US CLOs. Just 5.7% of CLO loans are in this sector (and about 1% is likely in supermarkets, a stable sub-sector). So, perhaps the retail risk is, shall we say, somewhat overstated.

demonstrates, the retail & supermarkets sector is the sixth largest industry exposure in US CLOs. Just 5.7% of CLO loans are in this sector (and about 1% is likely in supermarkets, a stable sub-sector). So, perhaps the retail risk is, shall we say, somewhat overstated.

But that’s not to say there is no risk. After all, cycles do cycle and the default rate will rise. And then we’ll see how the current loan vintage performs. This performance was a topic of animated discussion at Wednesday’s RMA seminar. After Ms. Coffey and Churchill’s Randy Schwimmer presented on Large Corporate and Middle Market trends, the panel dove into how loans’ Loss Given Default (LGD) may change. The panel noted that there are material differences between the 2007 and 2017 loan markets. First, there is far less leverage in the financial system, so a disorderly unwind is less likely. Second, leverage still is lower in 2017 deals (even when using unadjusted EBITDA) and companies themselves are better and stronger. But deal docs are looser, and therein lies the rub. First, thanks to add-backs, no one necessarily knows exactly what EBITDA is. Second, thanks to looser incremental debt provisions, the amount of debt at default (EAD or Exposure at Default) may well be higher. Third, with companies’ potential ability to transfer assets, the value of the collateral may be overstated. And, fourth, with less subordination, there is less debt below loans to absorb losses. All this suggests that, while Ds don’t seem to be moving quickly, when the cycle does turn, LGDs might be somewhat higher.