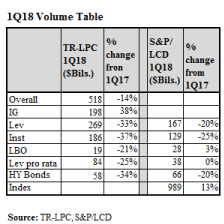

April 5, 2018 - To be fair, there is volatility out there. But in 1Q18, the loan space was a bastion of stability. At a high level, the primary leveraged loan market seemed actually slow(ish) – at least in comparison to the year-earlier period. As the volume table  illustrates, TR-LPC saw leveraged lending declining 33% from 1Q17 levels to $269 billion, while institutional lending slid 37% to $186 billion. S&P/LCD likewise saw a drop in leveraged lending (down 20% to $167 billion) and institutional lending (down 25% to $129 billion). Meanwhile, LFI tracked 1Q18 “priced deals” at $243 billion, off 28% from the year-earlier period.

illustrates, TR-LPC saw leveraged lending declining 33% from 1Q17 levels to $269 billion, while institutional lending slid 37% to $186 billion. S&P/LCD likewise saw a drop in leveraged lending (down 20% to $167 billion) and institutional lending (down 25% to $129 billion). Meanwhile, LFI tracked 1Q18 “priced deals” at $243 billion, off 28% from the year-earlier period.

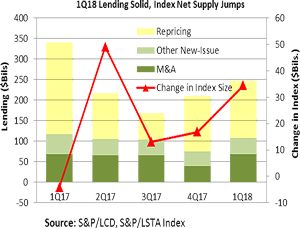

But these were “good” declines. The volume drop-off primarily reflects a reduction in the opportunistic repricing activity that defined first quarter 2017. (That’s not to say there was a dearth of such activity. As the Chart of the Week (COW) illustrates, there still was a non-trivial $143 billion of repricings – but this was far below 1Q17’s $224 billion.) Real lending, from sources like M&A, remained more stable. S&P/LCD saw LBO activity climb by 3% and overall M&A lending slip “only” 6% from 1Q18 levels. In turn, there was solid real supply. According to LFI, net priced volume (which measures “priced deals” minus their “associated repayments”) totaled $67 billion in 1Q18, up from $60 billion in 1Q17.

The better flow of real business was reflected in net supply figures gleaned from the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index. As the COW also demonstrates, the size of the index increased by $34 billion to $989 billion in 1Q18. In 1Q17, the Index size decreased by $4 billion to $880 billion.

In contrast, the demand side of the equation was rather similar in the two periods, albeit for different reasons. In 1Q17, there was $30 billion of net visible demand ($17 billion of CLO issuance and $13 billion of loan mutual fund inflows). In 1Q18, there was $35 billion of net visible demand ($31 billion of CLO issuance and $3.8 billion of loan mutual fund inflows).

Thus, the 1Q18 supply/demand imbalance was much better than in 1Q17. But there was, nonetheless, excess demand and that, of course, led to the inevitable term degradation. According to LCD’s Quarterly, average spreads on BB/BB- TLBs averaged LIB+228 in 1Q18, while B+/B TLBs averaged LIB+343; both are post-crisis lows. More dramatically, arrangers allocated more than $25 billion of paper priced at LIB+175, LFI added. But the news wasn’t all bad on the yield side. Although BB/BB- spreads contracted 11 bps over the quarter and B+/B spreads tightened 22 bps, three month LIBOR actually rose 60 bps, more than making up the difference. While many borrowers managed their borrowing costs by selecting one-month LIBOR, the benchmark’s recent rise still has had a material impact on loan “coupons”. Case in point: The effective yield on loans in the S&P/LSTA Index increased from 4.86% in December 2017 to 5.12% in March 2018.

Which brings us to the next question: At what point do rising interest rates begin to bite? Notwithstanding a jump to 2.42% due to iHeartCommunications’ bankruptcy, default forecasts currently remain benign. Meanwhile, interest coverage ratios remain very strong, with more than half the public filers in the S&P/LSTA Index seeing coverage ratios north of 4x. Still, LCD offered a word of warning. According to UBS research, the first 75-100 bps of Fed interest rate hikes should be easily absorbed by leveraged borrowers. But the second 100 bps could pressure leveraged companies, particularly B rated ones. And so, in due course, we’ll see if the Fed already has begun to take away the punch bowl.