May 31, 2018 - There are many things to do as the market prepares for a transition away from LIBOR. One of the first areas of focus is what happens in credit agreements if LIBOR ceases. As we discussed in the LSTA LIBOR Webcast on May 30th, for legacy deals, we encourage market participants to review 1) the long-term suitability of existing fallbacks in credit agreements and 2) the flexibility to amend agreements to select a new rate.

In most cases, before new rate replacement language started to appear last fall, the ultimate fallback in credit agreements was the prime rate and an amendment to change the interest rate might require 100% lender vote. For new deals, it is important to understand what new language is in the credit agreement. Given that the difference between LIBOR and Prime is currently more than 200 basis points, a long-term move to Prime could become a hardship for borrowers and yet successfully executing an amendment to select a new rate may prove infeasible.

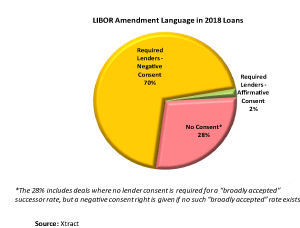

Trying to balance efficiency and equity, market participants have responded to potential LIBOR cessation by creating a streamlined amendment processes. While new amendment flexibility to select a replacement benchmark has become widespread, the language is not standard. That said, the new amendment language generally addresses three fundamental questions: 1) what are the trigger events? 2) who selects the new rate? 3) what is the level of lender involvement? We take each one in turn. Typically, the trigger events contemplate a permanent discontinuation of LIBOR, but there are a minority of deals that include an earlier trigger if LIBOR is no longer a widely recognized benchmark in the syndicated loan market. The decision as to whether a trigger event has occurred is most often determined by the agent, but the parties that select the rate may vary. A common formulation is for the borrower and administrative agent to select the rate together but instances of agent-only determination or agent determination in consultation with the borrower are also observed. The level of lender involvement in the selection of a replacement rate is the area of most variation.  As depicted in the nearby chart, Xtract data shows 70% of 2018 credit agreements grant Required Lenders (typically lenders holding more than 50% of the aggregate credit exposure) a negative consent right (i.e. a right to object) to the replacement rate chosen. However, 28% of 2018 deals do not grant Required Lenders any consent rights. (Caveat: The 28% include deals in which no lender consent is required for a “broadly accepted” successor rate, but a negative consent right is given if no such “broadly accepted” rate exists, and the agent and borrower must identify a successor on their own.)

As depicted in the nearby chart, Xtract data shows 70% of 2018 credit agreements grant Required Lenders (typically lenders holding more than 50% of the aggregate credit exposure) a negative consent right (i.e. a right to object) to the replacement rate chosen. However, 28% of 2018 deals do not grant Required Lenders any consent rights. (Caveat: The 28% include deals in which no lender consent is required for a “broadly accepted” successor rate, but a negative consent right is given if no such “broadly accepted” rate exists, and the agent and borrower must identify a successor on their own.)

It is important to note that the majority of amendment language includes comfort through safeguards, such as the requirement that the agent and borrower shall give due consideration to prevailing market convention or select a replacement rate that is widely accepted in the syndicated loan market. Indeed, assuming that SOFR is selected as the replacement rate, a credit spread adjustment will need to be added to minimize value transfer at the point of transition. Currently, less than 1% of deals done in 2018 explicitly contemplate a credit spread adjustment. As this journey continues and market participants learn more about the behavior of term SOFR vs. LIBOR, we can expect new fallback language to become increasingly specific and perhaps even become “hardwired” i.e. a yield-equivalent rate is automatically implemented upon specified trigger events. The evolution of fallback language is certainly a space to watch as this transition unfolds.

For further information, please send questions to LIBOR information@lsta.org. You can also find our Syndicated Loans and LIBOR FAQs on the LSTA website.