June 29, 2022 - It’s T-12 (months) for LIBOR. LSTA members hopefully know that LIBOR will finally and inexorably cease on June 30, 2023. As existing contracts expire around that date, all legacy loans will need to transition to their replacement rate. So, with just 12 months remaining, how has the LIBOR transition gone thus far – and what are the remaining major issues?

The transition. First, the transition from LIBOR to Term SOFR for new loan originations went remarkably well. But it wasn’t (only) luck! The smooth transition was largely due to many preconditions being met behind the scenes. First, unlike the UK, the ARRC recommended a Term SOFR rate. This short-circuited a battle over whether a credit sensitive rate (CSR) or a daily SOFR rate would prevail and permitted the loan market to quickly coalesce around CME Term SOFR. In addition, considerable effort went into ensuring that SOFR could be operationalized and documented. As a result, in the first five months of 2022, Refinitiv had tracked $900 billion of loans – including pro rata, middle market and investment grade loans – originated on Term SOFR. LCD added that that $142 billion (or 99%) of new institutional loans – excluding add-ons – were originated on Term SOFR in 1H22.

The outstanding issues. While the flip to Term SOFR moved smoothly, several issues remain. First, the Credit Spread Adjustment (“CSA”) debate continues. This is relevant for the economics of new issues as well some loans that fall back from LIBOR to SOFR using older, non-ARRC amendment fallback language. And, critically, there likely are $4 trillion-plus of syndicated loans that still need to transition from LIBOR to a replacement rate. For reasons discussed below, the early remediation of this “back book” has moved more slowly than might be optimal.

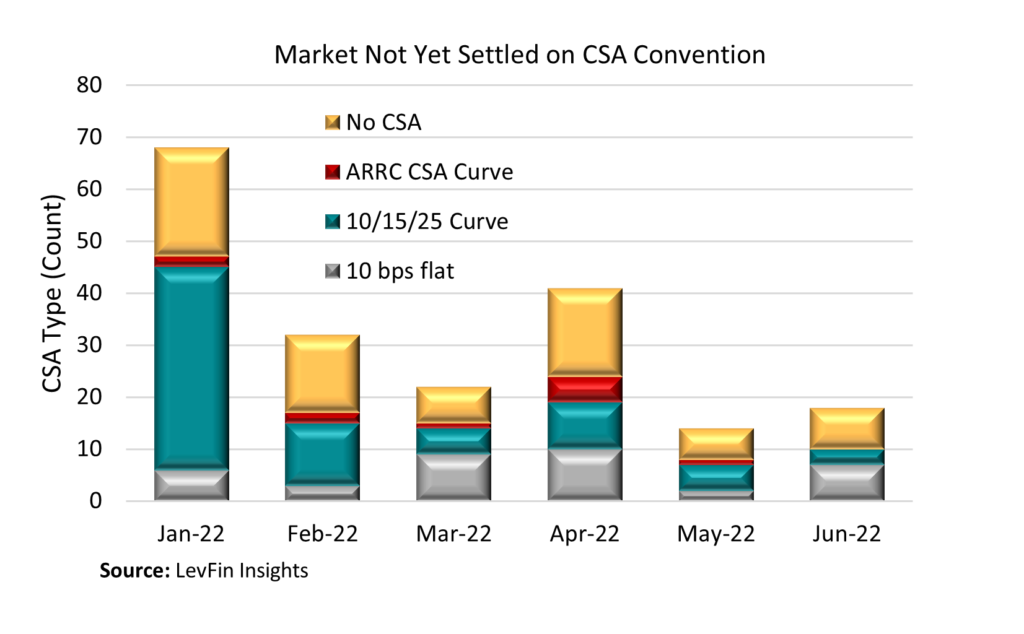

The CSAs. SOFR is a risk-free rate, while LIBOR is a credit sensitive rate. For this reason, the SOFR term curve generally should be i) lower and ii) flatter than the LIBOR term curve. In turn, loans that have hardwired “fallback” language use the ARRC spread adjustments (described below) to make SOFR loans more economically equivalent to LIBOR. A similar “CSA” mechanism was adopted into new loans for two reasons. First, it eases the transition process by creating transparency around whether new SOFR loans are roughly economically equivalent to LIBOR-based loans. Second, some older loans with pre-ARRC “amendment fallback” language may require the agent and the lender to look at the convention for SOFR loans generally when determining the fallback CSAs; thus, for some subset of loans falling back from LIBOR to SOFR, it may be important that new SOFR loans include a CSA. Unfortunately, there does not yet appear to be a single predominant convention on CSAs. As the COW demonstrates, there are a variety of different CSAs, including 10 bps flat across the curve (i.e., 10 bps for 1M/3M/6M tenors), a “market curve” (i.e., 10 bps for 1M/15 bps for 3M/25 bps for 6M) and an “ARRC fallback curve” (11 bps for 1M/26 bps for 3M/43 bps for 6M). There also are new loans that do not include any CSA, and theoretically embed the CSA into the loan margin. (“Theoretically” because if the “right” 3M CSA is 15 bps, one might expect more loans pricing at SOFR+415, SOFR+515, etc.) In June, 39% of loans used a flat 10 bps CSA, 17% used a “market” CSA and 44% used no CSA, reported LevFin Insights.

Remediation: It’s no one’s fault, but the remediation of the back book has been slower than many might like. The Shared National Credit (“SNC”) Review tracked $5.1 trillion in syndicated loans in 2021 (excluding non-bank private credit). Presumably, many of these loans i) are LIBOR-based and ii) have not yet transitioned to a replacement rate. Refinitiv estimates that, looking across all market segments, there may be 6,000 borrowers with loans still tied to LIBOR. Meanwhile, drilling down to the institutional loan market, BofA research on trustee reports suggest that just 12% of loans in CLOs are priced off SOFR. Ergo, there is a lot of wood to chop in the next 12 months.

There are several ways to transition early. First, a borrower may fully refinance or amend into a new SOFR loan, thus controlling all the terms of the new deal. However, this requires opening the credit agreement. With the average bid in the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index sitting below 94, opening up an existing credit agreement – and repricing a loan to a market clearing spread – simply isn’t attractive to companies.

Second, while most loans have the ability to use fallback language to “opt-in” early to SOFR, this has not yet been broadly executed. Such opt-ins typically require both borrower consent and required lender consent (negative or affirmative) and, for ARRC fallbacks, the economics of ARRC spread adjustments are not yet compelling for borrowers. Long story short, though lenders might want to move faster on transitioning their loan book, it may simply not be a high priority – or economically attractive – for borrowers.

What’s next: While it may not be a good time for early remediation, the reality is that $4 trillion-plus of syndicated loans need to be remediated in the next 12 months. And if folks wait until LIBOR cessation, the process could be…unwieldy. Those loans using hardwired fallbacks may have an easier time at LIBOR cessation – but they still will require conforming changes amendments. Meanwhile, loans with amendment fallbacks will require a (streamlined) amendment to transition – and, of course, such amendments could be blocked if required lenders rebel. If the loan market settles down – fingers crossed – remediation might come back into vogue. And that would be good for everyone.